Chapter 5

Bristol’s Tin-Glazed Earthenware Potteries

Introduction

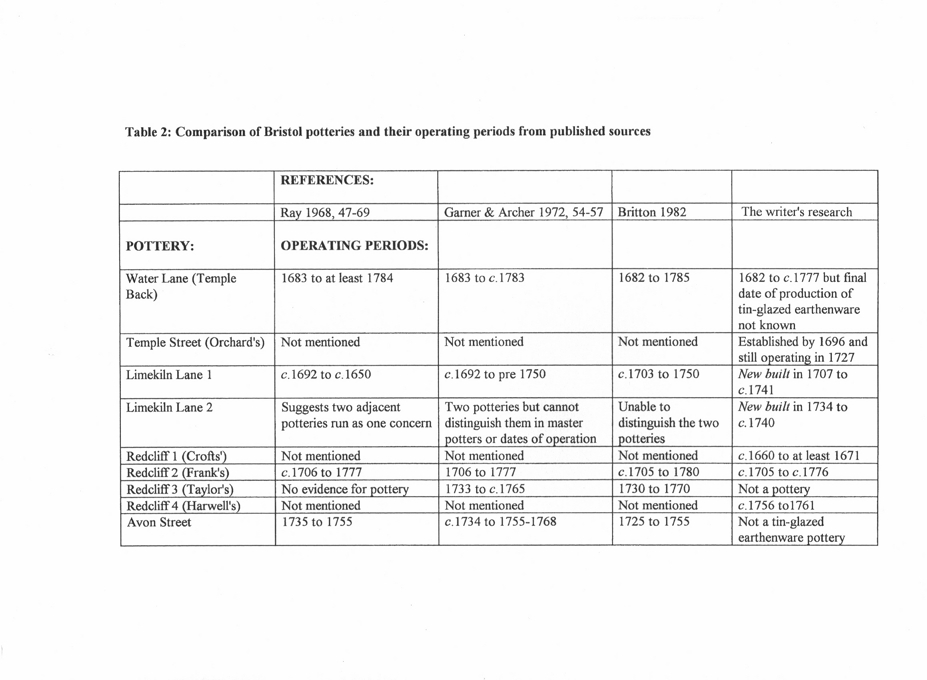

Two major books on tin-glazed earthenware production in Britain refer to the Bristol industry and each attempts to establish a chronology for the Bristol potteries (Ray 1968; Garner & Archer 1972). The authors based their statements on findings contained in the two authoritative published sources available – Owen and Pountney – while failing to carry out any new research themselves on the wealth of contemporary documents available. Even the most recent book on Bristol’s tin-glazed earthenware industry, Britton’s English Delftware in the Bristol Collection (1982), contained no new research on the origins and histories of the potteries.

In an endeavour to put in place a solid framework for the origins and development of the tin-glazed earthenware industry in Bristol the major documentary sources studied by Pountney – the apprenticeship and freedom records for the city – have been checked and a large number of new documentary sources studied. These sources are detailed in the ‘Documentary References’ section below and the results of the research were published in 1982 in the book Bristol Potters and Potteries 1600 – 1800 by R. & P. Jackson and R. Price. Since then further documentary research has been carried out by the writer and this chapter is a résumé and analysis of the current knowledge.

In his recent book on tin-glazed earthenware Michael Archer (1997, 564-565) based his chronology of the Brislington and Bristol potteries on information supplied to him by the writer. That chronology now requires up-dating in the light of the writer’s subsequent research.

Table 2 shows a comparison between the information on the Bristol potteries contained within Ray, Garner & Archer and Britton and the results of research carried out initially by Jackson, Jackson and Price and, more recently, by the writer alone. A number of discrepancies can be seen in the operating dates of particular potteries, the omission by others of potteries such as Mary Orchard’s in Temple Street and William Pottery’s in Limekiln Lane, and the erroneous inclusion of the Avon Street pottery which produced stoneware. Garner, Archer and Britton considered that Joseph Taylor and subsequent members of the Taylor family ran a tin-glazed earthenware pottery in Redcliff Street, while Ray was of the opinion that the Taylors’ premises was a shop selling earthenware rather than a manufactory. The writer’s research suggests that Ray was correct in his assumption, the rate books showing that Joseph Taylor was occupying two properties described as a shop and warehouse, not a pottery.

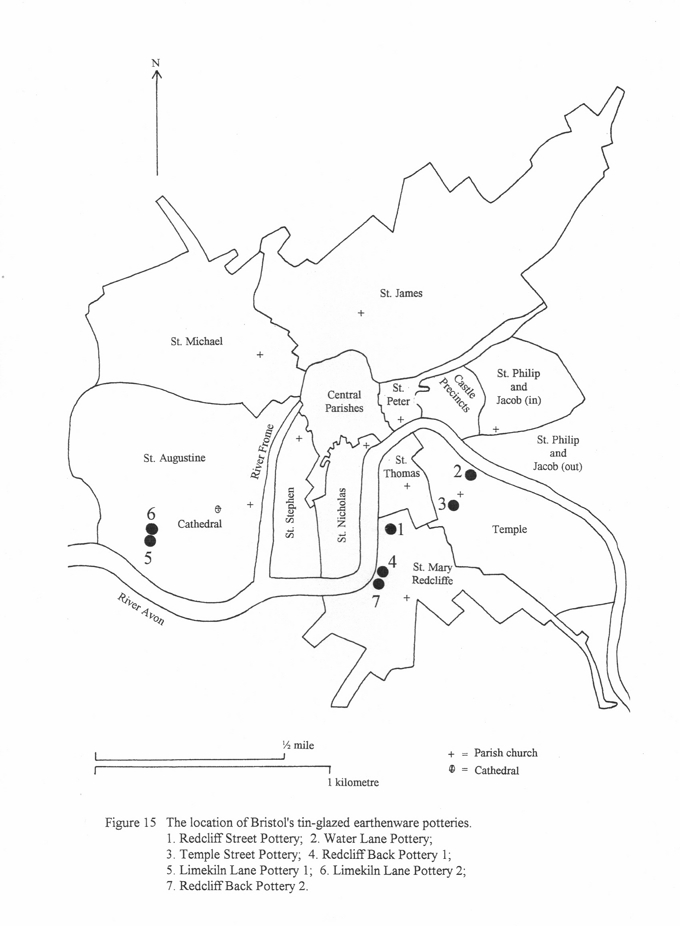

The potteries below are listed in chronological order of the date of their establishment in the city and their locations are shown in Fig. 15.

Redcliff Street Pottery (Fig. 15, No. 1)

In a record book of the Bristol Corporation known as the Mayor’s Orders, and dated 22 December 1660, there is a list of the inhabitants of St. Mary Redcliffe parish who were required to ‘hang out a Lanterne and Candle lighted at their respective doores during this season from six to nine of the clock evy. night’. One of those inhabitants was Edward Crofts who gave his trade as a potter. This is the earliest reference to a potter working in Bristol during the 17th century, although it is not clear whether he was producing tin-glazed earthenware. The next reference to him was five years later when, on 30 December 1665, he was described as a potter of St. Mary Redcliffe parish when he stood surety for a marriage licence granted to Joyhn Weston, a clothworker.

We are able to identify where Crofts lived in St. Mary Redcliffe parish as his property was owned by the Dean and Chapter of Bristol Cathedral and his lease on the property was renewed on 6 March 1668. It was described as ‘All that messuage or tenement … now in the tenure of Edward Croft situate in Redcliffe Street in St. Mary Redcliff parish between a tenement now or late in the holding of Thomas Gerry cooper on the one side and a tenement in the holding of the said Edward Croft on the other side together with all shops, cellars, sollars, halls, etc.’.

A tax assessment for St. Mary Redcliffe parish for the third quarter of 1668 listed an ‘Edward Crofte’ as paying rent on two properties in Redcliff Street, one described as a ‘Dwellinghouse’ and the other as a ‘work house’. Assuming that the ‘work house’ was a pottery, then Edward Crofts must have been manufacturing earthenware in his own right, rather than as an employee of another master potter.

It is possible that his workhouse/pottery was the property referred to in an agreement dated 18 January 1670 between Crofts and the Corporation of Bristol which stated that as ‘Edward Crofts, Potter, [had] lately builte upon the Citties waste on Redcliffe Backs the same being surveyed containes sixteene foote in breadth and six foote in width and being willing to hold and enjoy the same by grant from the Citie …’ a lease was to be granted to him on the land and building for a period of 99 years on the lives his wife Sarah and daughter Eliza.

By 2 May 1671, Edward Crofts’ dwelling house in Redcliff Street were described as being in the tenure of ‘Widow Crofts’ and from this we can assume that Edward Crofts had died between January 1670 and May 1671. It is possible his business was carried on by Sarah until her own death in 1687. Her will dated 9 November in that year shows that she was a lady of some substance, owning a ‘Dwelling house and garden … adjoyning conteyning by estimation One acre … situate in the North Streete of Bedm[inster], … Somerset’ which she left to her daughter Elizabeth, the wife of Edward Yeamans, a Bristol mariner. The tenement ‘where she now lived with widow Walker, John Grymes, Robert Castell and William Lancaster (part being void) in Redcliffe Street’ she left to her daughter, Sara, to whom she also left ‘fower Sandy pewter platters, one pewter plate, three pottingers, a paire of small grates, a looking glasse, one great brasse pottage pott, one little pottage pott, one little brass Kettle, Three Ruggs and all such other goods as I have already delived to her which shee hath locked upp in the Roomes over the [dwelling in Redcliff Street and also] fower joynt stooles, one table Board, and one Iron Back now being in the Dwelling house of Thomas Joines of the p’sh of Temple … weaver’.

We do not know what type of ware Crofts produced: he was always referred to as a potter rather than a gallypotmaker. Nevertheless, it is a possibility that Crofts was operating a tin-glazed earthenware pottery in Bristol in the 1660s and 1670s, some twenty-five years earlier than Edward Ward’s Water Lane pottery which is generally accepted as the earliest production site of such wares in the city.

The documentary evidence shows a clear connection between Edward Crofts and the tin-glazed earthenware potters at Brislington – if only on a personal rather than a business level. In her will of 1666, Anne Bissicke the widow of the tin-glazed earthenware potter John Bissicke of Brislington, made a number of bequests to the Crofts family. She gave to ‘Edward Croftes my great household Bible in token of my love’, to his wife, Sarah, ‘our small book called the Sanctuary of a Troubled Soule [and] one gold Deathes head ring’, and to his daughters, Sarah and Elizabeth,‘my silver cuppe with my husbands name and myne ingraven thereon, my small box of drawers’ and ‘tenne shillings in money to buy a ring’.

A study of the surviving leases, rate books and street directories for Redcliff Street carried out by Dr. Roger Price (pers. comm.) in connection with archaeological excavations in the street has enabled us to identify Crofts’ tenement as 108 Redcliff Street. This was located on the west side of the street, south of its junction with Ferry Street. Dr. Price has also identified Crofts’ ‘work house’ as being at 109 Redcliff Street, which adjoined his tenement to the south. The closest wharves on the River Avon, at Redcliff Back, were less than 100 metres west of his properties. The sites of Crofts’ tenement and work house now lie below Ferry Street, a recently widened version of what was a narrow lane connecting Redcliff Street with Redcliff Back, and it is possible that archaeological evidence for the pottery could remain below the modern road surface.

In 1986 Frank Britton published an article in the Transactions of the English Ceramic Circle concerning Edward Crofts, endeavouring to show that he was a Brislington potter (Britton 1986, 191-192). He suggested that Edward Crofts trained at either the Montague Close or Pickleherring potteries in London, and stated that ‘by the year 1660, the only two potters of whom we know at Brislington were Robert Collins and Edward Croft’. He went on to make the statement that ‘in the ten years from 1660 to 1670 Edward Croft must have been a very important figure in the Brislington pottery, being the only Southwark-trained potter there …’. None of these statements is supported by the documentary evidence currently available, but, in order to overcome the problem that Edward Crofts is mentioned in all the known documents as living and working in St. Mary Redcliffe parish, Britton asserted that while ‘we note that Croft was described as of St. Mary Redcliffe parish, … this was less than 2 miles from the [Brislington] pottery, which I do not think would have been regarded as too far to walk to work in those days’.

As yet there is no proof that Edward Crofts was a tin-glazed earthenware potter but, if he was, then all the evidence available shows he was working in Bristol, not Brislington.

The Water Lane (or Temple Back) Pottery (Fig. 15, No. 2)

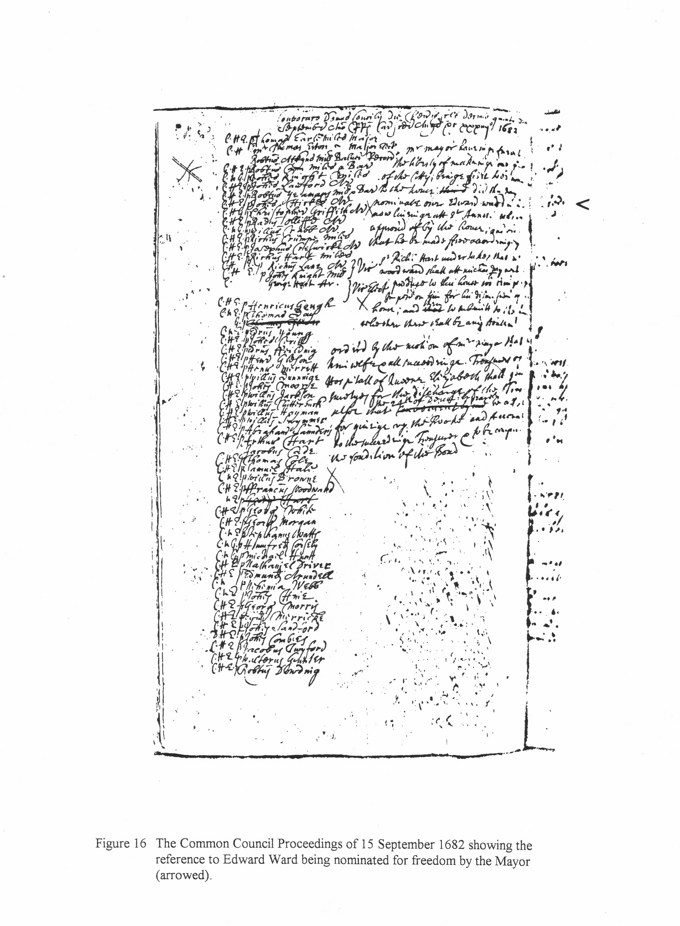

If Edward Crofts was not producing tin-glazed earthenware then the first pottery to produce such ware in the city was that established by Edward Ward in about 1682. We know that in September 1678 Ward was working as a ‘servant’ to Sarah Wastfield, the owner of the Brislington pottery. His admission to Bristol as a freeman seems to have been arranged by the Mayor of the city, who was allowed the privilege of nominating one person to become a freeman each year. It is perhaps some measure of the importance attached to the trade of tin-glazed earthenware manufacture in the late 17th century that, on 15 September 1682, Edward Ward was nominated for that honour and duly elected as a freeman, enabling him to carry on his trade in the city without the normal obligation of having to undergo a seven year apprenticeship (Fig. 16).

Edward Ward established his pottery on the south side of Water Lane in Temple parish, an area until then occupied by the Rack Close where cloth was stretched on racks to dry. It must be assumed that the pottery had started production by February 1683 when Edward took his son, also called Edward, as an apprentice to learn the trade of gallypotmaking. Edward Ward and the family members who carried on the Water Lane pottery after his death were referred to in documents as gallypotmakers so we can be fairly certain that tin-glazed earthenware was the main product of the Water Lane pottery.

There are various references to the property owned by Ward in Water Lane. The City Survey of 1700 referred to Ann Jordan and Edward Ward paying an annual rent of £1.12.8 for ‘2 Rack Closes now tenements’ and the Great Audit Book of the City Corporation for 1701 lists a rent of £1.6.2 received from ‘Edward Ward, potter, for tenmts’. In March 1692 the Temple parish churchwardens’ accounts record the receipt of ten shillings from Edward Ward for ‘halling through the parish wast’, presumably a reference to his disposal of waste materials from his pottery. In addition to the pottery site he was paying rates on ‘ye Mill at St. Anns’ in Brislington, between at least 1694 and 1703, which he presumably used for grinding colours. By 1704 the mill had passed into the occupation of Thomas Frank, the owner of the Redcliff Back pottery.

Edward Ward died in February 1710 and the pottery was taken over by his eldest son, Edward. Unfortunately, Edward Ward junior died shortly after in 1712 and on 16 January 1713 his three apprentices were transferred to his brother, James, who appears to have remained the proprietor of the pottery until 1732 when his son, Thomas, began paying rates on the premises. Thomas died in 1738 and his widow, Frances, carried on the business taking apprentices in December 1739 and July 1741.

In 1746 the pottery passed out of the Ward family and was taken over, first by Thomas Cantle, then by William Taylor in 1756 and by Richard Frank and Son in 1777. It is not known when tin-glazed earthenware production at the pottery ceased but ‘Delph Ware’, possibly a reference to tin-glazed earthenware, was included in an inventory of its stock in 1785. A number of owners ran the Water Lane pottery between 1784, when it was vacated by Richard Frank and Son, until its closure in 1886.

Ward’s pottery was established in Water Lane which runs east from Temple Street and, in the 17th century, it terminated on the west bank of the River Avon. It was here, on the south side of the lane, that Ward built his pottery on what had been open land. Subsequently, the area between the pottery and the bank of the tidal river was reclaimed and in the 18th century a street, Temple Back, was laid out parallel to the river. In the 18th century the Water Lane pottery expanded south along the Temple Back frontage, which accounts for it sometimes being referred to as the Temple Back pottery.

In the 1960s the site of the Water Lane pottery was cleared for redevelopment although, to the writer’s knowledge, the entrance yard to the pottery bounded by at least one standing pottery building survived until 1971. Despite the importance of the pottery in the story of Bristol’s ceramic industry, no archaeological excavation was carried out on any part of the site before an office block, The Crescent Centre, was built there in 1972. There is now no possibility of any part of the pottery surviving below ground.

However, in December 1972, a series of pits containing pottery was revealed in a service trench being dug by building contractors along the west side of Temple Back (Price forthcoming). Eleven pits were excavated, some producing only miscellaneous sherds of post-medieval pottery, but five pits yielded well-defined groups of pottery kiln waste. As none of the waste material was associated with a kiln it is not possible to state with absolute certainty where it was made, but there can be little doubt that it came from the Water Lane pottery. The two most important 18th-century groups of waste sherds and kiln furniture came from pits found within the probable boundaries of the 18th-century factory: a good indication that this was the site of their manufacture. These pits produced the most extensive and important groups of tin-glazed earthenware wasters to be recovered archaeologically in Bristol. They are believed to date to the period c.1730 to 1760 which coincides with the end of the period when the Ward family were in ownership, followed by the time when Thomas Cantle and later William Taylor were the proprietors of the Water Lane pottery.

Temple Street Pottery (Fig. 15, No. 3)

A pottery was established in Temple Street, in Temple parish, around 1696 by Mary Orchard whose trade was described in contemporary documents as either a potter, potmaker, mugmaker or gallypotmaker. The latter terminology tends to confirm that the pottery was producing tin-glazed earthenware although probably in addition to other types of ware; Pountney and Ray being of the opinion that redware and brown-glazed stoneware was also being manufactured. Certainly the term ‘mugmaker’ usually seems to refer to the production of stoneware mugs or tankards. The apprentice records show that her apprentices were to be taught the art of gallypotmaking, potmaking, mugmaking and glass or white glass making, so the production of her pottery was obviously quite diverse.

The Mary Orchard who established the business was almost certainly the Mary Suter of St. Mary Redcliffe parish who was granted a licence to marry John Orchard, a sailor of Devon, at St. James’ Church in Bristol on 13 June 1668. On 7 March 1684 John Suter was granted a lease on a tenement and garden on the west side of Redcliff Street by the feoffees of the lands owned by St. Mary Redcliffe church. By 1698 Mary was listed as a widow when paying church rates on the premises, her husband having died during the intervening period.

It was at about this time that, with an unspecified number of un-named co-partners, she embarked on the potting trade, as she is listed as exporting pottery in the 1696 Port Book. The Port Book entries are important as they confirm that her pottery was in production two years before her previously known operating date, that of taking her first apprentice, John Bye, on 14 May 1698. The identity of the co-partners, who probably financed her business, was unknown until the recent discovery by the writer of a property lease dated 20 March 1701. This suggests that one of the co-partners was a Bristol merchant called William Andrews, a party to the lease with Mary Orchard, the lease being taken out on the property owned by John Knight of New Sarum in Wiltshire and described as ‘All that Messuage or Tenement of him the said John Knight scituate lyeing and being in Temple Streete in the parish of Temple … Together with all the Garden Stable Potthouse and warehouse thereto belonging lately erected and built And alsoe all and singular Roomes Kitchens halls parlours Chambers Sollars Shopps Lofts Lights pavements wayes water Easements …’. The lease permitted ‘the said William Andrews and — Orchard their Executors Adminstrs and Assignes to erect in the same part of the said Garden one or more potthouse or potthouses’ and the annual rent was set at £35. It appears from this document that there may already have been a pothouse on site before it was leased by Mary Orchard and William Andrews and that they intended to erect further kilns. The possibility of William Andrews’ involvement as one of Orchard’s co-partners is reinforced by references in the Bristol Port Book of 1700 to a William Andrews exporting quantities of earthenware in his own name to various destinations in Ireland and the West Indies (PRO E/190/1158/1).

The involvement of these co-partners seems to have been short-lived. Mary Orchard took her first apprentice in association with the co-partners in 1698 but by 1702, when she took her next apprentice, she did so alone and this was the case with her remaining eight apprentices taken over the following eighteen years. Her last apprentice, William Adlam, took his freedom in 1727 having served his term of seven years, so we can assume that Mary Orchard was still carrying on her trade from the Temple Street pottery until that date at least. She died in December 1730 and was buried in the churchyard at St. Mary Redcliffe; her will made in 1721 makes no reference to her trade although one of her executors was the tin-glazed earthenware potter Thomas Frank, owner of the Redcliff Back pottery.

It has not been possible to identify the location of Mary Orchard’s pottery. Temple Street was one of the main north/south thoroughfares, Redcliff Street being another, which ran through the adjoining parishes of Redcliff and Temple. The street was bisected and partly obliterated by Victoria Street which was laid out in the 1860s. What remains of Temple Street has been widened and the properties fronting it largely redeveloped, so there is now little possibility of Orchard’s pottery being located and excavated.

Redcliff Back Pottery 1 (Fig. 15, No. 4)

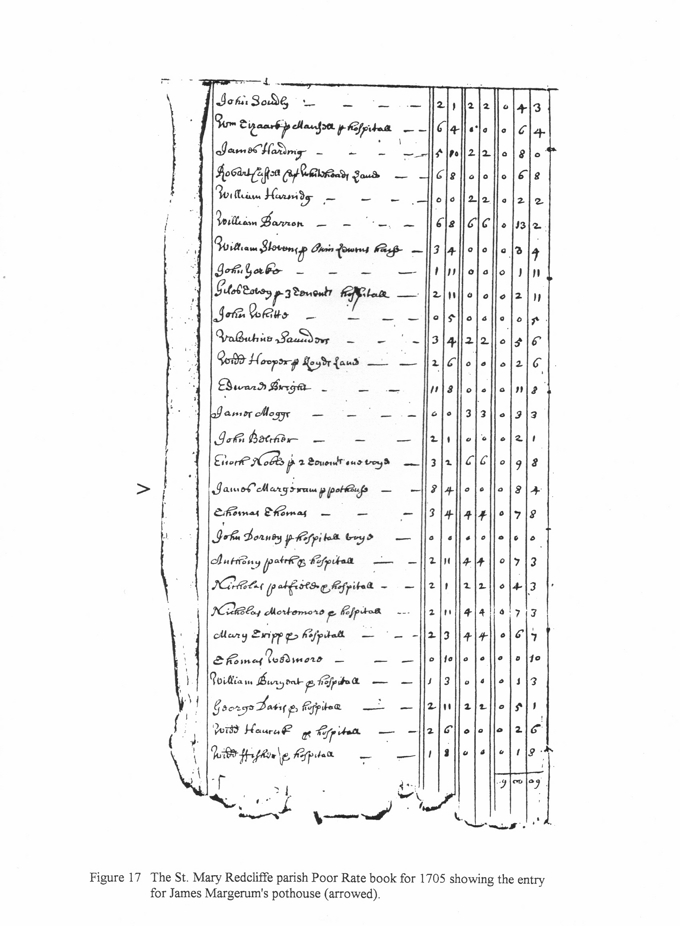

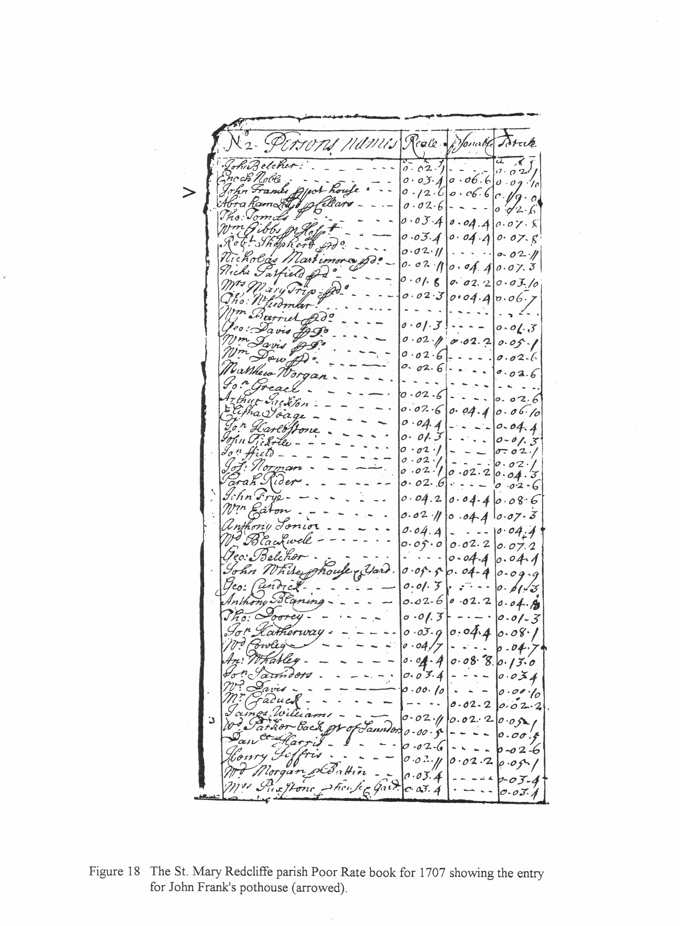

The account books detailing the collection of the Land Tax and Poor Rate in St. Mary Redcliffe parish are important to our understanding of the early history of this pottery. Although a number of account books are missing, sufficient remain to show that the collectors of the Land Tax and Poor Rate listed the properties in the same sequence in each book so that tracing the history of a property from year to year is relatively straightforward. In this way we know that the site of the Redcliff Back pottery was occupied by William Clark’s glasshouse in 1700 but the next surviving Poor Rate book, for 1705, shows it as by then being occupied by a ‘pothouse’ owned by James Margerum (Fig. 17), although nothing else is known of Margerum as a potter. By 1707 John Franks was paying rates on the pothouse and he did so the following year (Fig. 18). Again nothing else is known about John Franks and it is possible this was a clerical error for Thomas Frank who is shown as occupying the pothouse in 1709.

In 1689 Thomas Frank was apprenticed to the tin-glazed earthenware potter Edward Ward at the Water Lane pottery, taking his freedom as a gallypotmaker in 1698. Frank took his first apprentice on 11 July 1698, although it is not known where he was working at that time. Frank did not take another apprentice until 1707 by which time he had probably started working at Redcliff Back. In the documents Thomas Frank was usually referred to as a gallypotmaker suggesting that the Redcliff Back pottery was producing tin-glazed earthenware.

In addition to the pottery on Redcliff Back he was paying rates on a warehouse on Redcliff Back, houses in Redcliff Hill and Cathay and a garden in Guinea Street. In 1704 he was also paying rates to the churchwardens of St. Luke’s in Brislington for ‘ye Mill’, presumably used for grinding colours, which he took over from Edward Ward, owner of the Water Lane pottery.

Thomas Frank’s son, Richard, had been apprenticed to his father in 1727 and took his freedom in 1727 as a gallypotmaker. By 1738 he must have had a financial interest in the pottery as he started paying Land Tax on the premises jointly with his father, taking an apprentice in his own right in 1741. By 1750 Thomas Frank had stopped paying rates on the pottery, probably because he had retired from business, although he did not die until 1757. The pottery was then taken over by Richard who, from 1750, was paying rates on the premises alone.

Richard Frank continued as sole proprietor at the pottery until 1766 when the Lamp and Scavenging rate returns show that he had been joined in business by his son, Thomas, and they continued paying rates jointly until 1776. They had vacated the premises by August 1776 when a lease from the Corporation to John Morgan, Thomas Lawrence and Joseph Hill referred to ‘all those premises formerly a Potthouse now converted into Sundry dwellings’.

One 12 June 1777 the Bristol Gazette newspaper recorded that: ‘Richard Frank & Son, earthen and Stone Pot Works, are removed from Redcliff Backs to Water Lane, where they continue the same business in all its Branches’. (see Water Lane pottery, above)

A clue as to the location of the pottery is given in an advertisement for the premises which appeared in the Bristol Gazette on 29 May 1777: ‘To be lett … a house and several large warehouses, situated on Redcliff Back adjoining the River Avon, now and for many years past in the Occupation of Messrs. Frank & Co., Potters – The premises lie close to the River, where there is a Slip for landing goods, and are very well adapted for the business of a Potter … or any other Business that requires Room …’. Redcliff Back stretched north from the low cliff of red sandstone (from which the parish of St. Mary Redcliffe derived its name) below Redcliff Hill and Redcliff Parade to a point where it joined Redcliff Street, a distance of some 400 metres. Redcliff Back ran parallel to the bank of the Avon and it is clear from the newspaper advertisement that Frank’s pottery must have been on the west side of the street, adjoining the river. We know from a surviving plan that Richard Frank’s house was situated on the west side of Redcliff Hill and that the house and its extensive rear garden extended along the top edge of the sandstone cliff. Dumps of tin-glazed earthenware wasters have been noted in the man-made cave system tunnelled into the cliff and which extends below the site of Frank’s house and garden. It seems likely that these wasters derive from Frank’s pottery which was probably situated at the south end of Redcliff Back, close to the cliff and overlooked by Frank’s residence. That area is now a large open quayside and it is possible that parts of the pottery complex survive below the modern ground surface.

Limekiln Lane 1 (‘The Lower Pothouse’) (Fig. 15, No. 5)

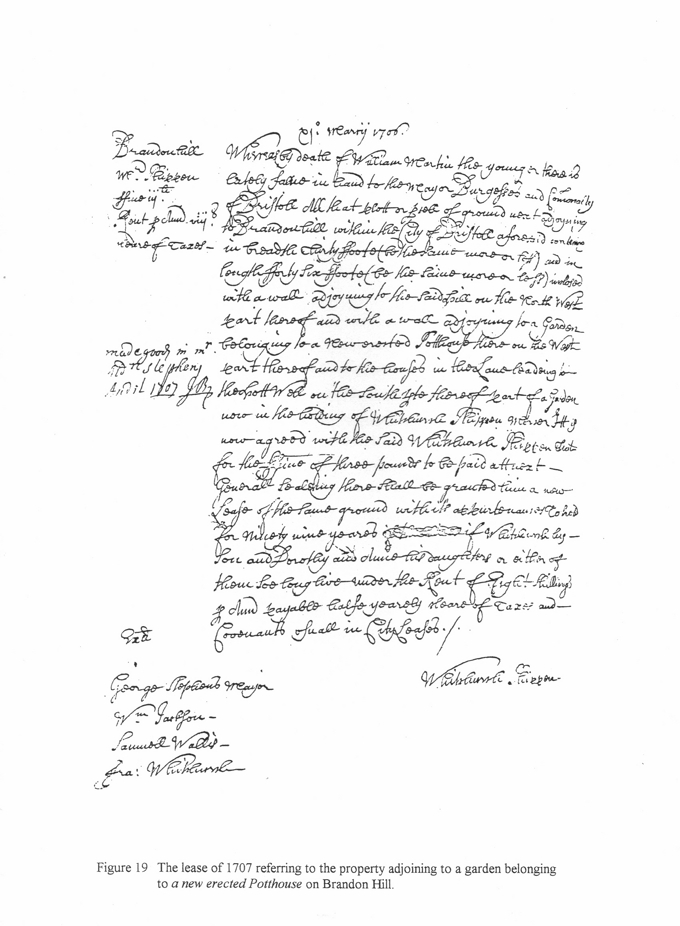

Limekiln Lane, sometimes called Cow Lane, in St. Augustine’s parish, was situated one kilometre west of the centre of Bristol and the pottery was located on the north side of the lane on the lower slopes of Brandon Hill, some 200 metres from the River Avon. On 13 February 1693, Henry Hobbs, a Bristol house-carpenter and member of the Society of Friends, was granted a lease by the Corporation of Bristol on ‘Two Gardens wall’d in with a washhouse, summerhouse, and app’tennes thereto belonging lying under Brandon Hill …’. Under the terms of this lease Henry Hobbs was to spend one hundred pounds on new buildings and he was allowed to quarry stone from Brandon Hill; thus the cost of building and equipping the pottery represented a considerable capital outlay. Hobbs paid rent on the property from 1694 and it was here that the pottery was built, although the precise dates of its construction and commencement of production are not known. The pottery was in existence by 1706 when the Land Tax return records ‘Mr Hobbs house and Potteworke messuages, etc.’ and a lease of 1707 refers to ground ‘adjoyning to a Garden belonging to a new erected Potthouse’ (Fig. 19).

The pottery was sufficiently well established by 27 November 1706 for Hobbs, now described as a ‘pottmaker’, together with an un-named co-partner, to take Daniel Annis as his first apprentice. As yet no evidence has been found to support the assumption made by Pountney (1920, 352) that the co-partner was Woodes Rogers, a Bristol privateer of the day.

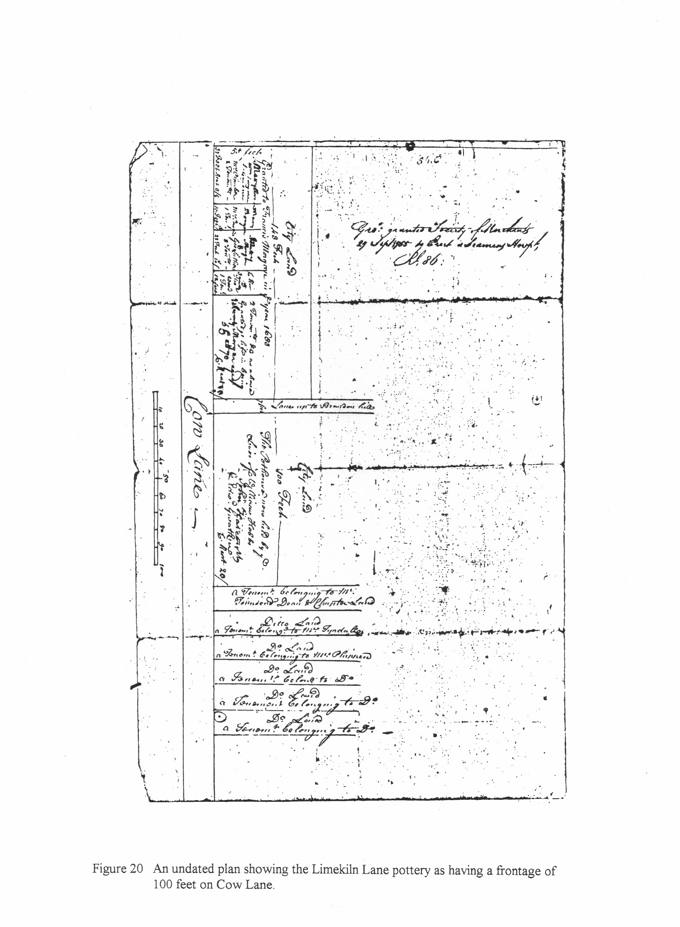

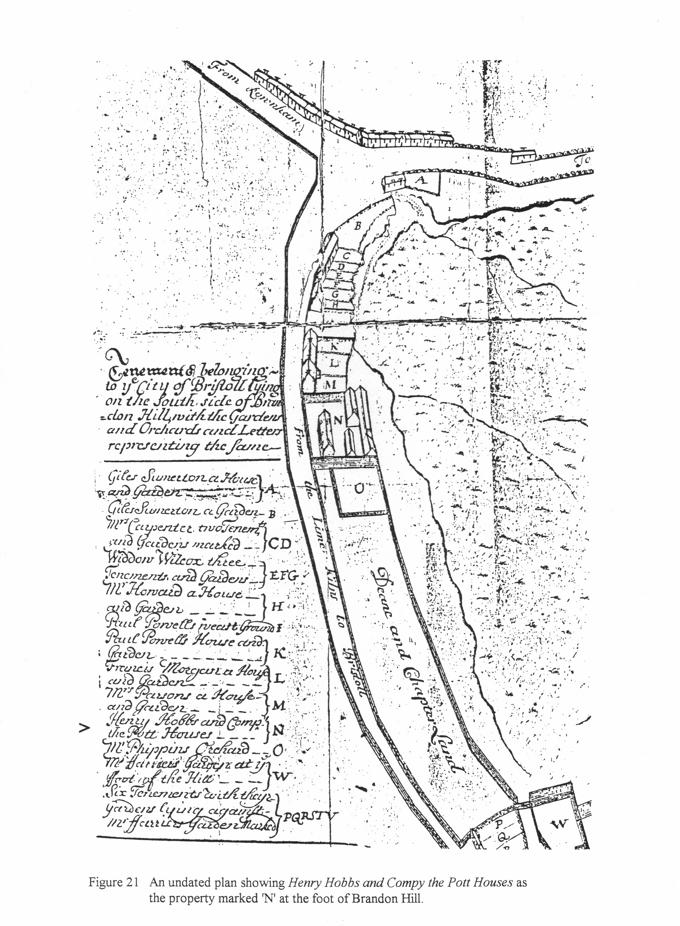

Two undated but contemporary plans show the location and size of the pottery. The first (Fig. 20) shows ‘The Pothouse’ as having a frontage of 100 feet (33 metres) on Cow Lane. The second plan shows the properties bordering Brandon Hill and names the owners and occupiers. The property marked ‘N’ on the plan (Fig. 21) is described as being ‘the Pott Houses’ occupied by ‘Henry Hobbs and Compy’. (This plan discussed further in Chapter 2, above).

Hobbs took eight apprentices between 1706 and 1716, and was variously described in the apprenticeship records as a potter, potmaker or gallypotmaker. He continued paying Land Tax and other rates on a ‘Potwork and dwelling house …’ until 1723. After Hobbs left the pottery it was occupied jointly by William Pottery and John Weaver, the Scavenging Rate returns for 1728/9 recording ‘Pottery & Weaver for the Pothouse’ (Fig. 22). William Pottery and John Weaver took nineteen apprentices between them before leaving the premises in 1734. After that date there are no further references to John Weaver but William Pottery went on to establish a second pottery in Limekiln Lane (see Limekiln Lane Pottery 2, below).

Charles Christopher then became the master potter and five of Weaver’s apprentices were transferred to Christopher to serve out the remainder of their term of apprenticeship. Christopher continued paying Land Tax on the pottery until September 1737 when the tax returns show it as ‘void’, although the pottery can only have been unoccupied for a short period for, by September 1739, Josiah Bundy had taken over the premises and he probably worked there until the end of 1741 when one of his apprentices was transferred to another potter. It is not clear whether the pottery was working after this date but it had probably ceased operation by July 1746 when it was advertised for sale in The Bristol Oracle newspaper: ‘To be Lett or Sold, And Enter’d upon immediately, The Lower Pot-House, In Lime-Kiln Lane, With Stock in Trade … ‘. In 1755 the land and ‘building for a pothouse’ was leased to the Society of Merchants; it was intended that they would build a hospital for seamen on the site but this project never came to fruition.

The existence of 18th-century plans showing the position of the pottery have enabled it to be located with certainty on a site now occupied by St. George’s House on the north side of St. George’s Road – the modern name for Limekiln Lane.

Tin-glazed earthenware wasters have been found on a number of occasions on Brandon Hill in the vicinity of the Limekiln Lane potteries, although these finds of kiln material have either come from disturbed surface deposits or from a quarry where the wasters had apparently been redeposited after being uncovered during building work: thus all must be considered as unstratified in archaeological terms.

In 1920, W.J. Pountney recorded that when buildings were being erected on the site of the Limekiln Lane potteries the workmen removed much soil containing sherds of saggars, drug jars and other vessels, and used this material to fill a quarry on the south side of Brandon Hill (Pountney 1920, xxxii). The exact location of this quarry is unknown. Pountney states that some of this redeposited material was later recovered by a local antiquarian, Alfred Selley. The buildings referred to by Pountney may have been St. George’s House or the adjoining terraced houses in Queen’s Parade, which date from the first quarter of the 19th century.

In 1939, H.W. Maxwell published details of his excavations at a site on Brandon Hill which was described as being south-west of the quarry mentioned by Pountney. He uncovered large quantities of wasters which were found close to the surface. He felt that the wasters had simply been dumped on the surface of the hill at the back of the potteries and had become covered with a thin layer of soil washed down the hill. Lipski (1969, 149) refers to digging being undertaken on the hill after 1948 and he was given the finds from that work when he excavated the same site a few years later. In 1972, during reseeding of the southern slopes of Brandon Hill considerable quantities of kiln furniture and wasters were found and recovered by Messrs Bennett and Cooper (Fowler 1973, 61). Apparently two sherds of soft paste porcelain dating c.1700 to1740 were found at the same time. Very abraded sherds of tin-glazed earthenware wasters can still be found lying on the surface of Brandon Hill just to the north of Queen’s Parade, especially where the turf has been worn away exposing the sub-soil.

In 1984 the site immediately to the east of St. George’s House was redeveloped and is now occupied by Jacob’s Court. When the front walls of the cellars adjacent to Queen’s Parade on the north, uphill, side of the site were removed, large quantities of kiln wasters could be seen in the exposed section. This section was 12 metres in length and 3.6 metres in depth at its deepest point and, beneath a layer of modern disturbance some half a metre thick, the section was almost entirely made up of kiln debris, in which some distinct tip-lines and lenses of ash could be seen. The finds, comprising tin-glazed earthenware wasters, both glazed and biscuit wares, and kiln furniture, have been published (Jackson & Beckey 1991) and deposited in the Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery under accession number 35/1984. A date range of c.1715 to 1725 has been suggested for this group which would place its production within the period when Henry Hobbs and Company were operating the pottery.

The site of the pottery itself was probably completely destroyed during the construction of St. George’s House, which was built on a terrace cut into the hillside.

Limekiln Lane Pottery 2 (‘The Upper Pothouse’) (Fig. 15, No. 6)

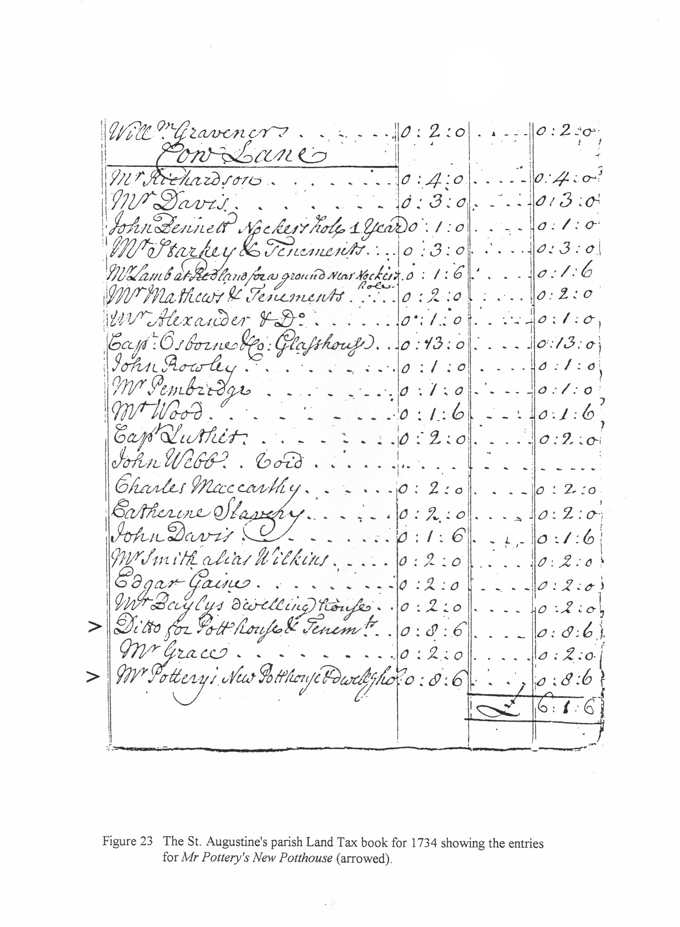

The reference in the 1746 Bristol Oracle advertisement to ‘The Lower Pot-House’ (see Limekiln Lane Pottery 1, above) is interesting as it implies the existence of another pottery in Limekiln Lane, perhaps located higher up Brandon Hill. We know that when William Pottery left ‘The Lower Pot-House’ in 1734 he established his own pottery very close by, although the exact location is not known. The Land Tax returns for St. Augustine’s parish list the persons paying the tax in the same order each year and this regular pattern appears to follow the sequence of properties in Limekiln Lane. It is significant that in the tax returns there is only one other entry dividing those for the two potteries and this reinforces the suggestion that they were in close proximity (Fig. 23).

The Land Tax returns of 1734 and 1735 for Limekiln Lane refer to ‘Mr. Pottery’s New Potthouse …’ and he continued paying tax on that property until 1740 when the return shows ‘Wm. Pottery for Potthouse void’, the word ‘void’ indicating it was unoccupied. Unfortunately, the Land Tax returns do not survive after 1740 but no later reference has been found to this second pottery.

As with Limekiln Lane 1, it seems certain that the ‘Upper Pothouse’ was destroyed during the construction of the houses along the south side of Queen’s Parade, all of which have cellars cut into the bedrock.

Redcliff Back Pottery 2 (Fig. 15, No. 7)

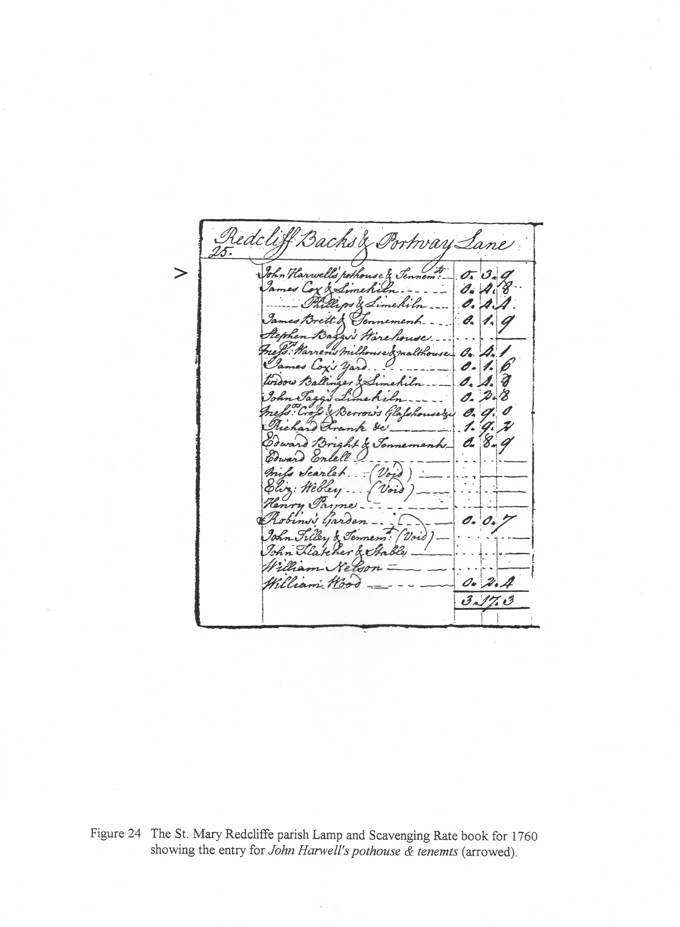

John Harwell obtained his freedom as a gallypotmaker in 1740 having been apprenticed to Joseph and Sarah Taylor. Between 1756 and 1760 he was paying rates on a property variously described as ‘John Harwells warehouse’ and ‘John Harwell’s pothouse & tenemts’ in Redcliff Back (Fig. 24). He took an apprentice in 1758 which coincides with his occupation of the property on Redcliff Back and suggests that he was running a pottery there.

The 1760 Poor Rate and Watch Rate returns for St. Mary Redcliffe parish show that the pottery had been taken over by Richard Frank, the property being described in the Poor Rate as ‘Richard Frank stone pot house’ and in the Watch Rate as ‘Richard Frank’s Small Pot House’. By 1761 the Watch Rate lists the property as ‘Richard Frank’s pot house void’ showing that the premises were unoccupied.

These entries, although confusing, certainly refer to the same premises, and it is clear that a second, small pottery was operating in Redcliff Back from about 1756 until 1761, occupied first by John Harwell and, after about 1759, by Richard Frank in addition to his main factory. It is possible that this pottery was producing tin-glazed earthenware during part of its period of operation, although the description of it as a ‘stone pot house’ (that is, one that was producing stoneware) may be significant.

It is not possible to locate the pottery from the limited documentary evidence available, although it was probably situated close to the Franks’ main pottery at the south end of Redcliff Back.

A Summary of the Potters Involved in the Bristol Potteries

Redcliff Street Pottery

- Edward Crofts: c.1660 to at least c.1671

Water Lane (Temple Back) Pottery

- Edward Ward I: 1682 to 1710

- Edward Ward II: 1710 to 1712

- James Ward: 1712 to 1732

- Thomas Ward: 1732 to 1738

- Frances Ward: 1738 to 1746

- Thomas Cantle: 1746 to 1756

- William Taylor: 1756 to 1777

- Richard and Thomas Frank: 1777 to 1784

Temple Street Pottery

- Mary Orchard: c.1696 to at least 1727

Redcliff Back Pottery 1

- James Margerum: c.1705

- John Frank (possibly a mistake for Thomas Frank): c.1707 to 1708

- Thomas Frank: 1709 to 1738

- Thomas and Richard Frank: 1738 to 1750

- Richard Frank: 1750 to 1766

- Richard and Thomas Frank: 1766 to c.1776

- Richard and Thomas Frank then took over the Water Lane pottery

Limekiln Lane 1 (‘The Lower Pothouse’)

- Henry Hobbs: c.1707 to 1723

- John Weaver and William Pottery: 1723 to 1734

- Charles Christopher: 1734 to 1737

- Josiah Bundy: c.1739 to c.1741

Limekiln Lane 2 (‘The Upper Pothouse’)

- William Pottery: 1734 to c.1740

Redcliff Back Pottery 2

- John Harwell: c.1756 to 1760

- Richard Frank: 1760 to 1761

Conclusions

It is possible that Edward Crofts, who had personal connections with the Brislington potters, had established a tin-glazed earthenware pottery in Bristol by about 1660. Certainly Edward Ward had moved from Brislington to Bristol in 1682 to establish his pottery at Water Lane in Temple parish. The increasing demand for tin-glazed earthenware, particularly from the developing markets in Ireland, the West Indies and North America, led to the founding of at least a further four potteries in the city in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. These were all built on the fringes of the city near already established industrial concerns such as glassmakers and limeburners and where inhabitants were unlikely to be annoyed by smoke from the kilns. They were also situated close to the River Avon which could be used for the transport of raw materials and finished goods.

A theme running through the early history of these potteries was the non-conformist religion of the proprietors: the Frank family of the Redcliff Back pottery and Henry Hobbs of Limekiln Lane 1 pottery were all Quakers and it seems likely that Edward Ward was also a Nonconformist – his son, Edward, was certainly a Baptist. This coincides with the Nonconformity of some of the key potters working at Brislington in the 17th and 18th centuries.